- Home

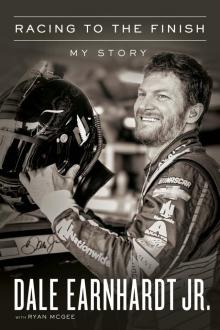

- Dale Earnhardt Jr

Racing to the Finish

Racing to the Finish Read online

© 2018 DEJ Management, LLC

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or other—except for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published in Nashville, Tennessee, by W Publishing, an imprint of Thomas Nelson.

Thomas Nelson titles may be purchased in bulk for educational, business, fundraising, or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected].

Any Internet addresses, phone numbers, or company or product information printed in this book are offered as a resource and are not intended in any way to be or to imply an endorsement by Thomas Nelson, nor does Thomas Nelson vouch for the existence, content, or services of these sites, phone numbers, companies, or products beyond the life of this book.

Epub Edition September 2018 9780785221968

ISBN 978-0-7852-2160-9 (HC)

ISBN 978-0-7852-2196-8 (eBook)

ISBN 978-0-7852-2669-7 (SE)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018949131

Printed in the United States of America

18 19 20 21 22 LSC 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Information about External Hyperlinks in this ebook

Please note that footnotes in this ebook may contain hyperlinks to external websites as part of bibliographic citations. These hyperlinks have not been activated by the publisher, who cannot verify the accuracy of these links beyond the date of publication.

To my wife, Amy Earnhardt, who gave me

strength, support, and Isla Rose.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD BY DR. MICHAEL “MICKY” COLLINS

A LIFT, A SECRET, AND A PROMISE

1. HAMMERHEAD

2. INTO THE FOG

3. BACK ON TRACK

4. THE CLOUD RETURNS

5. THE LOST SEASON

6. HARD TRUTHS

7. BATTLEGROUND OF THE MIND

8. TO RACE OR NOT TO RACE

9. THE RETURN . . . AND THAT OTHER R-WORD

10. SEND HER AROUND ONE MORE TIME

DON’T BE A HAMMERHEAD

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

PHOTOS

FOREWORD

I first met Dale Earnhardt Jr. in 2012 when he was worried and anxious to return to the racecar. When I saw him again in 2016, he was riddled with physical and emotional symptoms from his multiple concussions, petrified and desperate to simply return to life.

Recovering from his injuries took tremendous effort and commitment, all in the face of overwhelming pressure to return to his beloved sport. He is one of the hardest-working patients I have ever treated. He worked tirelessly on his rehabilitation. It quickly became obvious to me that we were not only treating Dale and his injury but also the incredible forces surrounding his desire to please his fans, his family, his owners, and his legacy.

Dale has a strong tendency to think of others before thinking of himself. The title of this book, Racing to the Finish, is an interesting choice, as the decision of whether to retire played a ubiquitous role in every aspect of his care and outcome. I recognized that very early with Dale, but as I told him so many times, my only priority was for him to feel normal again. The rest would take care of itself.

As a clinician in charge of his care, I never really worried about the return-to-racing issue; I was much more focused on his living his life without the burden of and hypervigilance about his debilitating symptoms. Fortunately, we were successful in that regard. Yes, Dale faced many challenging moments, but I was always extremely confident that our treatments would prove effective and that he would get to the finish line. The fact that Dale recovered and returned to racing before retiring “on his own terms” (what I told him so many times) makes me so proud. Even more important is that Dale walked down the aisle symptom-free and married Amy, the love of his life.

In typical Dale fashion, the primary reason he is bravely sharing his story is for others to receive help with their similar injuries. Concussions afflict millions of pediatric, adult, geriatric, and military patients. During a typical day at our clinic at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), we will see dozens of children and adults who are suffering from chronic symptoms and dysfunction associated with concussion. The majority of these individuals have not received any targeted treatment for difficulties that directly affect physical, social, vocational, and psychological functioning, even though we now agree as a field that concussion is a treatable injury. You’ll read in this book about our UPMC model that reveals six different clinical profiles, or types, of concussions. Each of them requires active and targeted treatments to improve outcomes. We have and will continue to publish research proving the efficacy of this model.

As you will see from Dale’s treatment, the field of concussion has evolved dramatically over the past few decades. The days of dark rooms and complete rest following this injury are being replaced with active physical therapies and targeted treatments that allow recovery to fully occur. Unfortunately, the science and evidence-based information represent a collective whisper buried in the cacophony of sensationalized and overwhelming media attention that leads to misinformation and a misunderstanding of concussion. As our recently commissioned Harris Poll indicated, 25 percent of parents prevent their children from playing sports because of concerns of concussions; a large majority of US adults believe you can only lessen symptoms and that you never fully recover; and they are not comfortable that they would know the steps to manage and treat a concussion if they sustained one.1

Dale’s story is a call for action and change. Progress is being made, and Dale is a living testament to that. He has shared his story to better educate those who have experienced this injury and to accurately share that effective treatments are available. Even prior to this book, his story was making a difference. Many patients have told me they sought treatment at our clinic after hearing about Dale’s case and recovery.

I am grateful to our incredible team at UPMC, including our researchers, athletic trainers, physical therapists, and treating clinicians. I also want to thank Dr. Petty, who delivered exemplary care to Dale and referred him to our clinic. Dr. Petty and I spent many hours in person and on phone calls working together to get Dale back in his racecar and back to life. He is such a caring and incredibly talented clinician. I also want to thank Kelley, Dale’s sister, for her support, as well as Rick Hendrick for providing the free rein to allow Dale to recover fully. Rick’s sole motivation was to see Dale healthy and well, and I truly respected that. And finally, Amy was unwavering and tough, a formidable assistant when it came to Dale completing his physical therapies. She provided constant love and support during his recovery. I can see how they are a perfect fit for each other. I will never forget the personal text I received from Dale following little Isla Rose’s birth. He was so grateful and full of pride and joy. Dale’s moving on with his life as a family member, husband, and father is what this was all about all along.

Congrats on your recovery, Dale, you earned it. It was an absolute privilege to work with you.

Dr. Michael “Micky” Collins

Director, UPMC Sports Medicine

Concussion Program

June 2018

A LIFT, A SECRET, AND A PROMISE

Sunday, May 4, 2014

Talladega Superspeedway

We were having a good day at Talladega, NASCAR’s biggest, most intimidating racetrack. If you know anything about my NASCAR career, then you know that me and that place, we’ve always had a

special relationship. I won there six times. My father won there ten times. The Earnhardts and Talladega, we’ve grown up together. There’s a whole generation of fans down there who were raised to root for me, taught by the generation before them, who rooted for my dad.

So whatever I did when I raced at Talladega was always a really big deal, good or bad. If the grandstand felt like I was making a move to the front, they would lose their minds. Even with forty-plus cars out there roaring around, I could hear them cheering. If they felt like I had been done wrong, I could hear them booing too. I loved it.

On this day, I had them rocking a couple of times. We led a bunch of laps and spent nearly half the day running up inside the top ten. Now, late in the race, they were waiting on me to make my move. So was my team in the pits, especially my crew chief, Steve Letarte. Just a few months earlier we’d won the Daytona 500. But for whatever reason we had never won together at Talladega. Today we really believed we had a chance to fix that.

But now, late in the race, I was stalled. We made a pit stop for fuel and I got stuck in the pack. I was boxed into my position with nowhere to go. With eight laps to go, I was setting up for my move to the front, but a slower, underfunded car moved in front of me.

At Talladega, you have to have a dance partner to team up with, to split the air, slip through it, and move up through the pack. But this car in front of me now, this was a bad dance partner. There was no way I could push that car to the front. Heck, there was no way I could push any of these cars around me to the front. I was jammed up, running three-wide in basically a 200-mph parking lot with nowhere to go.

I started doing the math in my head. How many laps were left? What was my running position? How many cars did I need to slide by to get back into the lead? I added all of that up and realized that the best I was going to do was get up into the top fifteen. Maybe.

So . . . I lifted.

I did. I backed off and got out of there. I jumped on the radio and I told my team that I thought there was going to be a big crash and I was staying back so I could stay out of it and steer around it when it happened. At Talladega we call it the Big One, when a pack of cars, just like the one I was running in right now, all wreck at once. Cars start spinning and there’s smoke everywhere and you have no idea where you are going, what you are going to hit, or what’s going to hit you. Even when you do think you’re about to steer clear of it all, a car—or a wall—can come out of nowhere.

I didn’t want any part of that. Not today. So, yeah, I lifted my right foot out of the throttle and I let my Chevy ease back out of that pack. I watched them all move out ahead of me and then made sure to give them their distance, but not too far. I stayed close enough that I could still hang on to their draft, staying on the back edge of that aerodynamic bubble that would keep me close, but not too close. There were twenty-seven cars on the lead lap, and I settled into twenty-sixth. If they started wrecking, I would have enough room and time to get around that mess without getting hurt.

To be clear, this is a strategy that a lot of drivers have used over the years, but they always did that at the start of the race, not with a few laps to go like I was doing. They hung back waiting to make a dramatic late move. I wasn’t going to make any moves. My only move was to stay safe.

That was my whole goal. Don’t get hurt. Not again.

There’s a famous NASCAR story about Bobby Isaac, the 1970 NASCAR Cup Series champion. A few years later, in the middle of a race at Talladega, Bobby came over the radio and told his team to get a relief driver ready because he was getting out of there. He pulled down pit road, climbed from his car, and walked straight to a pay phone and called his wife. Bobby told her that a voice had spoken to him, clear as a bell, and told him to get out of the car. Earlier in that same race, an old friend of his, Larry Smith, had gotten killed. Bobby was done. He didn’t race again that season and only ran Talladega one more time. Looking back, that was really the day that his Hall of Fame career ended.

Riding out those final few laps that day at Talladega, there weren’t any mysterious voices in my head. The only voice I heard was my own. I felt awful about what I was doing. It went against everything that being a racer is about. I knew I was going to have to answer questions about it, not just from my fans but from my team. But none of them knew what I had been going through that month. No one did. Not even my fiancée, Amy.

They did know what I had endured nearly two years earlier, on August 29, 2012. Everyone did. During a tire test at Kansas Speedway I hit the wall going 185 mph and suffered a concussion that eventually forced me to get out of the car for two races later that season.

After I returned, everything went pretty much back to normal until one month before this Talladega race. On Monday, April 7, 2014, at the high-speed Texas Motor Speedway, I finished dead last after wrecking on lap 12. It was a bizarre situation. I was running down the frontstretch, blinded a little by the car in front of me, and my left front tire ran off the asphalt and into the infield grass. It was a mistake on my part, but it wasn’t all that unusual. What was unusual was that it had rained all weekend and that patch of grass was like a mud bog. The way we were building our racecars, they rode super low to the ground. So, when I hit that soaked turf with a nearly two-ton machine at 200 mph, the grass grabbed that corner of my car and instantly folded it in. It bent that sheet metal and steel like it was nothing, like it was a cardboard box. It grabbed so hard my car actually went up in the air for a split second before slamming back down onto the blacktop. Now riding on only three tires, my car veered right and smacked the outside retaining wall, once . . . twice . . . three times . . . and then kind of dot-dot-dotted its way along the wall.

If you were watching that race on TV and saw my crash, you probably remember the fact that the car caught on fire. When I finally got the car stopped and climbed out over the hood, the whole rear end of my Chevy was up in flames. But you probably wouldn’t have thought much of the size of all those impacts. If you’re a race fan or a racecar driver, then you’ve seen or experienced hits just like that all the time.

For me, though, it was like an old wound had been opened. All of a sudden, my brain went back to showing symptoms I hadn’t felt since 2012. They weren’t as intense as what had forced me out of the car two years earlier; they were much subtler. But I knew something wasn’t right. I knew it instantly.

I told no one. Amy knew I didn’t feel well because she’s the one who has to look after me every day, but I didn’t share everything with her either. The only place where I exposed the true details of what I felt was in the notes app on my iPhone. The morning after the Texas crash, I opened that app and started regularly writing out the details of whenever I felt bad. I’ve been doing it ever since. A journal of symptoms.

At first, I don’t think I even really understood why I started doing it. This sounds morbid, but when I look back now I realize that what I was doing was leaving a trail for others to discover in case something happened to me that kept me from being able to tell them myself.

I’ve never shared these notes with anyone until now. This is what I wrote in the days following that April 2014 Texas crash, just a few weeks before my decision to lift at Talladega. The notes start in the medical center at the racetrack, where every driver is required to visit following a crash, no matter how big or small, to be checked out by a doctor. From the track medical center it was home, then to a test session at Michigan Speedway, and then off to Darlington Raceway for the next event. These notes, the first I jotted down, are the vicious cycle I found myself living in after every hit on the racetrack:

Instantly in the infield care center I felt foggy. No pain or headache but felt a little foggy and quite a bit trapped.

Went home feeling a slight headache and visual issues like erratic eye movement. Not being able to focus on a single point or object. More than slight air-headedness or grogginess.

Spent night on couch with Amy. Got tired and went to bed. Felt trapped in my head some, but

just slightly. Couldn’t focus or remember simple things. Worried about my head all the time and couldn’t plug into my surroundings.

Groggy head Tuesday AM, over 12 hrs after accident. Emotional frustrations then too.

Cleared up mostly by afternoon, 24 hrs after event. Felt almost 100% by dinner but was tired and ready for bed by 9.

Slept well and woke up feeling happy and solid. Hardly no worry about head. Plugged into all surroundings. Happy disposition. Wednesday by noon felt a-ok.

Wednesday noon, still some slight mental mistakes or slip-ups. Walked into a clear glass wall I thought was a door while focusing hard on racing mural, looking for my car in it. Could be a “throw it in the concussion bin” moment but I think it’s still just a slight lack of mental sharpness that will be better by Friday.

Test session . . . both Tuesday and Wednesday, when I was in the car I felt sharper than when I wasn’t. But when I drove on highway Tuesday with sunglasses I felt odd and not sharp. Removing sunglasses makes it much better.

5 pm Wednesday: test is done, felt solid in the car all day. Feel good now riding to airport. Have slight pressure pains in my head that last a second or two but really feel good and clear in my thoughts.

Thursday morning. Wake up at home with headache. Clear mind.

Had head pressure all day really.

Friday. First day 100% solid. By Saturday I have forgotten about any issues.

This all happened barely seven weeks after winning the Daytona 500. We’d started the season with three consecutive top-two finishes. The weekend before Texas I’d finished third at California Speedway. I was off to one of the best starts of my career, in my seventeenth full season in NASCAR’s top division. We felt like we had a real shot at finally winning my elusive first season championship. There was no way I was going to let another concussion interrupt that.

Then, even after all of that trouble and worry at Talladega, I went to one of NASCAR’s most challenging ovals, Darlington Raceway, and finished second. One week later I finished seventh at Richmond International Raceway.

Racing to the Finish

Racing to the Finish